I. THE WELFARE STATE

Although the UK had won the war, the country was exhausted economically and the people wanted change. During the war, there had been significant reforms to the education system and people now looked for wider social reforms. In 1945 the British people elected a Labour government. The new Prime Minister was Clement Atlee, who promised to introduce the welfare state outlined in the Beveridge Report. In 1948, Aneurin (Nye) Bevan, the Minister for Health, led the establishment of the National Health Service (NHS), which guaranteed a minimum standard of health care for all, free at the point of use. A national system of benefits was also introduced to provide ‘social security’, so that the population would be protected from the ‘cradle to the grave’. The government took into public ownership (nationalised) the railways, coal mines and gas, water and electricity supplies.

Another aspect of change was self-government for former colonies. In 1947, independence was granted to nine countries, including India, Pakistan and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). Other colonies in Africa, the Caribbean and the Pacific achieved independence over the next 20 years.

The UK developed its own atomic bomb and joined the new North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), an alliance of nations set up to resist the perceived threat of invasion by the Soviet Union and its allies.

Britain had a Conservative government from 1951 to 1964. The 1950s were a period of economic recovery after the war and increasing prosperity for working people. The Prime Minister of the day, Harold Macmillan, was famous for his ‘wind of change’ speech about decolonisation and independence for the countries of the Empire.

Clement Attlee (1883–1967)

Clement Attlee was born in London in 1883. His father was a solicitor and, after studying at Oxford University, Attlee became a barrister. He gave this up to do social work in East London and eventually became a Labour MP. He was Winston Churchill’s Deputy Prime Minister in the wartime coalition government and became Prime Minister after the Labour Party won the 1945 election.

He was Prime Minister from 1945 to 1951 and led the Labour Party for 20 years.Attlee had inherited a country close to bankruptcy after the Second World War and beset by food, housing and resource shortages; despite his social reforms and economic programme, these problems persisted throughout his premiership, alongside recurrent currency crises and dependence on US aid. His party was narrowly defeated by the Conservatives in the 1951 general election, despite winning the most votes. He continued as Labour leader but retired after losing the 1955 election and was elevated to the House of Lords; after a long retirement, he died in 1967. In public, he was modest and unassuming, but behind the scenes his depth of knowledge, quiet demeanour, objectivity and pragmatism proved decisive. Often rated as one of the greatest British prime ministers, Attlee’s reputation among scholars has grown, thanks to his creation of the modern welfare state and involvement in building the coalition against Stalin in the Cold War. He remains the longest-serving Labour leader in British history.

Attlee’s government undertook the nationalization of major industries (like coal and steel), created the National Health Service and implemented many of Beveridge’s plans for a stronger welfare state. Attlee also introduced measures to improve the conditions of workers.

William Beveridge (1879–1963)

William Beveridge (later Lord Beveridge) was a British economist and social reformer. He served briefly as a Liberal MP and was subsequently the leader of the Liberals in the House of Lords but is best known for the 1942 report Social Insurance and Allied Services (known as the Beveridge Report). The report was commissioned by the wartime government in 1941. He was considered an authority on unemployment insurance from early in his career, served under Winston Churchill on the Board of Trade as Director of the newly created labour exchanges, and later as Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Food.

He was Director of the London School of Economics and Political Science from 1919 until 1937, when he was elected Master of University College, Oxford. Beveridge published widely on unemployment and social security, his most notable works being: Unemployment: A Problem of Industry (1909), Planning Under Socialism (1936), Full Employment in a Free Society (1944), Pillars of Security (1943), Power and Influence (1953) and A Defence of Free Learning (1959). He was elected in a 1944 by-election as a Liberal MP (for Berwick-upon-Tweed); following his defeat in the 1945 general election, he was elevated to the House of Lords where he served as the leader of the Liberal peers.

It recommended that the government should find ways of fighting the five ‘Giant Evils’ of Want, Disease, Ignorance, Squalor and Idleness and provided the basis of the modern welfare state.

Lord Butler (1902–82)

Richard Austen Butler (later Lord Butler) was born in 1902. Born into a family of academics and Indian administrators, Butler enjoyed a brilliant academic career before entering Parliament in 1929. As a junior minister, he helped to pass the Government of India Act, 1935. He strongly supported the appeasement of Nazi Germany in 1938–39. Entering the Cabinet in 1941, he served as Education Minister (1941–45, overseeing the Education Act 1944). When the Conservatives returned to power in 1951 he served as Chancellor of the Exchequer (1951–55), Home Secretary (1957–62), Deputy Prime Minister (1962–63) and Foreign Secretary (1963–64).

Butler had an exceptionally long ministerial career and was one of only two British politicians (the other being John Simon, 1st Viscount Simon) to have served in three of the four Great Offices of State but never to have been Prime Minister, for which he was passed over in 1957 and 1963. At the time, the Conservative Leadership was decided by a process of private consultation rather than by a formal vote. After retiring from politics in 1965, Butler was appointed Master of Trinity College, Cambridge. He became a Conservative MP in 1923 and held several positions before becoming responsible for education in 1941. In this role, he oversaw the introduction of the Education Act 1944 (often called ‘The Butler Act’), which introduced free secondary education in England and Wales. The education system has changed significantly since the Act was introduced, but the division between primary and secondary schools that it enforced still remains in most areas of Britain.

Dylan Thomas (1914–53)

Dylan Thomas was a Welsh poet and writer. He often read and performed his work in public, including for the BBC. His most well-known works include the radio play Under Milk Wood, first performed after his death in 1954, and the poem Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night, which he wrote for his dying father in 1952. He died at the age of 39 in New York. There are several memorials to him in his birthplace, Swansea, including a statue and the Dylan Thomas Centre.

Thomas came to be appreciated as a popular poet during his lifetime, though he found earning a living as a writer difficult. He began augmenting his income with reading tours and radio broadcasts. His radio recordings for the BBC during the late 1940s brought him to the public’s attention, and he was frequently used by the BBC as an accessible voice of the literary scene. Thomas first travelled to the United States in the 1950s. His readings there brought him a degree of fame, while his erratic behaviour and drinking worsened. His time in America cemented his legend, however, and he went on to record to vinyl such works as A Child’s Christmas in Wales. During his fourth trip to New York in 1953, Thomas became gravely ill and fell into a coma, from which he never recovered. He died on 9 November 1953. His body was returned to Wales, where he was interred at the churchyard of St Martin’s in Laugharne on 25 November 1953.

II. MIGRATION IN POST-WAR BRITAIN

Rebuilding Britain after the Second World War was a huge task. There were labour shortages and the British government encouraged workers from Ireland and other parts of Europe to come to the UK and help with the reconstruction. In 1948, people from the West Indies were also invited to come and work. During the 1950s, there was still a shortage of labour in the UK.

Further immigration was therefore encouraged for economic reasons, and many industries advertised for workers from overseas. For example, centres were set up in the West Indies to recruit people to drive buses. Textile and engineering firms from the north of England and the Midlands sent agents to India and Pakistan to find workers. For about 25 years, people from the West Indies, India, Pakistan and (later) Bangladesh travelled to work and settle in Britain.

III. SOCIAL CHANGE IN THE 1960s

The decade of the 1960s was a period of significant social change. It was known as ‘the Swinging Sixties’. There was growth in British fashion, cinema and popular music. Two well-known pop music groups at the time were The Beatles and The Rolling Stones. People started to become better off and many bought cars and other consumer goods. It was also a time when social laws were liberalised, for example in relation to divorce and to abortion in England, Wales and Scotland. The position of women in the workplace also improved. It was quite common at the time for employers to ask women to leave their jobs when they got married, but Parliament passed new laws giving women the right to equal pay and made it illegal for employers to discriminate against women because of their gender.

The 1960s was also a time of technological progress. Britain and France developed the world’s only supersonic commercial airliner, Concorde. New styles of architecture, including high-rise buildings and the use of concrete and steel, became common.

The number of people migrating from the West Indies, India, Pakistan and what is now Bangladesh fell in the late 1960s because the government passed new laws to restrict immigration to Britain. Immigrants were required to have a strong connection to Britain through birth or ancestry. Even so, during the early 1970s, Britain admitted 28,000 people of Indian origin who had been forced to leave Uganda.

IV. SOME GREAT BRITISH INVENTIONS OF THE 20TH CENTURY

Britain has given the world some wonderful inventions. Examples from the 20th century include:

The television – was developed by Scotsman John Logie Baird (1888–1946) in the 1920s. In 1932 he made the first television broadcast between London and Glasgow.

Radar – was developed by Scotsman Sir Robert Watson-Watt (1892–1973), who proposed that enemy aircraft could be detected by radio waves. The first successful radar test took place in 1935.

Working with radar led Sir Bernard Lovell (1913–2012) to make new discoveries in astronomy. The radio telescope he built at Jodrell Bank in Cheshire was for many years the biggest in the world and continues to operate today.

A Turing machine – is a theoretical mathematical device invented by Alan Turing (1912–54), a British mathematician, in the 1930s. The theory was influential in the development of computer science and the modern-day computer.

Insuline – the Scottish physician and researcher John MacLeod (1876–1935) was the co-discoverer of insulin, used to treat diabetes.

The structure of the DNA molecule – was discovered in 1953 through work at British universities in London and Cambridge. This discovery contributed to many scientific advances, particularly in medicine and fighting crime. Francis Crick (1916–2004), one of those awarded the Nobel Prize for this discovery, was British.

The jet engine – was developed in Britain in the 1930s by Sir Frank Whittle (1907–96), a British Royal Air Force engineer Officer.

Hovecraft – Sir Christopher Cockerell (1910–99), a British inventor, invented the hovercraft in the 1950s.

Concorde – Britain and France developed Concorde, the world’s only supersonic passenger aircraft. It first flew in 1969 and began carrying passengers in 1976. Concorde was retired from service in 2003.

The Harrier jump jet – an aircraft capable of taking off vertically, was also designed and developed in the UK.

ATM – In the 1960s, James Goodfellow (1937–) invented the cash-dispensing ATM (automatic teller machine) or ‘cashpoint’. The first of these was put into use by Barclays Bank in Enfield, north London in 1967.

IVF (in-vitro fertilisation) therapy – for the treatment of infertility was pioneered in Britain by physiologist Sir Robert Edwards (1925–) and gynaecologist Patrick Steptoe (1913–88). The world’s first ‘test-tube baby’ was born in Oldham, Lancashire in 1978.

Cloning – In 1996, two British scientists, Sir Ian Wilmot (1944–) and Keith Campbell (1954–2012), led a team which was the first to succeed in cloning a mammal, Dolly the sheep. This has led to further research into the possible use of cloning to preserve endangered species and for medical purposes.

Magnetic resonance imaging – Sir Peter Mansfield (1933–), a British scientist, is the co-inventor of the MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scanner. This enables doctors and researchers to obtain exact and non-invasive images of human internal organs and has revolutionised diagnostic medicine.

The inventor of the World Wide Web – Sir Tim Berners-Lee (1955–), is British. Information was successfully transferred via the web for the first time on 25 December 1990.

V. PROBLEM IN THE ECONOMY IN THE 1970s

In the late 1970s, the post-war economic boom came to an end. Prices of goods and raw materials began to rise sharply and the exchange rate between the pound and other currencies was unstable. This caused problems with the ‘balance of payments’: imports of goods were valued at more than the price paid for exports.

Many industries and services were affected by strikes and this caused problems between the trade unions and the government. People began to argue that the unions were too powerful and that their activities were harming the UK. The 1970s were also a time of serious unrest in Northern Ireland. In 1972, the Northern Ireland Parliament was suspended and Northern Ireland was directly ruled by the UK government. Some 3,000 people lost their lives in the decades after 1969 in the violence in Northern Ireland.

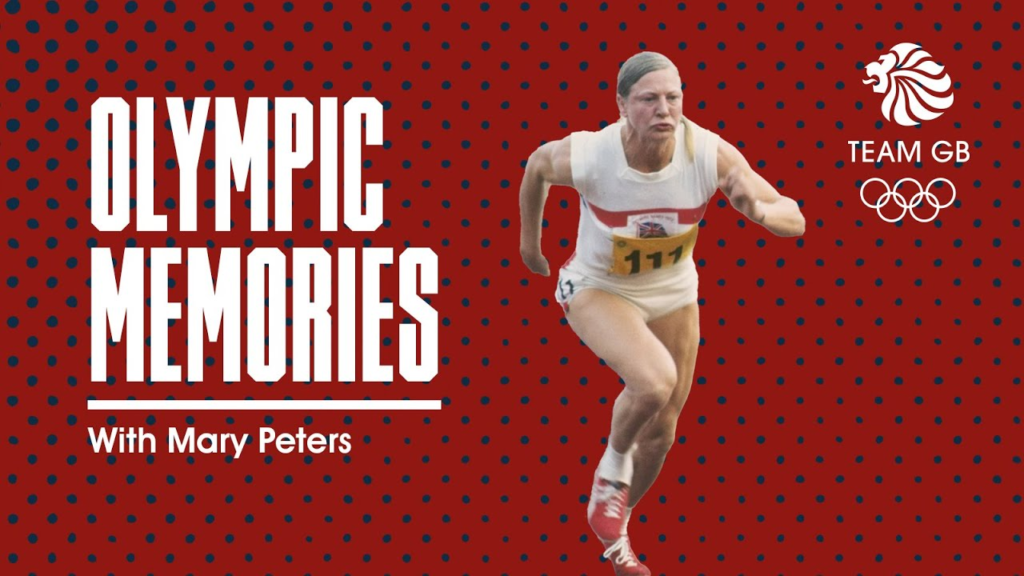

Mary Peters

Born in Manchester, Mary Peters moved to Northern Ireland as a child. She was a talented athlete who won an Olympic gold medal in the pentathlon in 1972. After this, she raised money for local athletics and became the team manager for the women’s British Olympic team. In the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich, Peters competing for Great Britain and Northern Ireland won the gold medal in the women’s pentathlon. She had finished 4th in 1964 and 9th in 1968. To win the gold medal, she narrowly beat the local favourite, West Germany’s Heide Rosendahl, by 10 points, setting a world record score.

After her victory, death threats were phoned into the BBC: “Mary Peters is a Protestant and has won a medal for Britain. An attempt will be made on her life and it will be blamed on the IRA … Her home will be going up in the near future.” But Peters insisted she would return home to Belfast. She was greeted by fans and a band at the airport and paraded through the city streets, but was not allowed back in her flat for three months. Turning down jobs in the US and Australia, where her father lived, she insisted on remaining in Northern Ireland. In 1972, Peters won the BBC Sports Personality of the Year award. “Peters, a 33-year-old secretary from Belfast, won Britain’s only athletics gold at the Munich Olympics. The pentathlon competition was decided on the final event, the 200m, and Peters claimed the title by one-tenth of a second.”

She represented Northern Ireland at every Commonwealth Games between 1958 and 1974. In these games she won 2 gold medals for the pentathlon, plus a gold and silver medal for the shot put. She continues to promote sport and tourism in Northern Ireland and was made a Dame of the British Empire in 2000 in recognition of her work.

VI. EUROPE AND THE COMMON MARKET

West Germany, France, Belgium, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands formed the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1957. At first the UK did not wish to join the EEC but it eventually did so in 1973. The UK is a full member of the European Union but does not use the Euro currency. In 1975, the United Kingdom held its first ever national referendum on whether the UK should remain in the European Communities.

The governing Labour Party, led by Harold Wilson, had contested the October 1974 general election with a commitment to renegotiate Britain’s terms of membership of the EC and then hold a referendum on whether to remain in the EC on the new terms. All of the major political parties and the mainstream press supported continuing membership of the EC. However, there were significant divides within the ruling Labour Party; a 1975 one-day party conference voted by two to one in favour of withdrawal, and seven of the 23 cabinet ministers were opposed to EC membership, with Harold Wilson suspending the constitutional convention of Cabinet collective responsibility to allow those ministers to publicly campaign against the government.

VII. MARGARET THATCHER

Margaret Thatcher was the daughter of a grocer from Grantham in Lincolnshire. She trained as a chemist and lawyer. She was elected as a Conservative MP in 1959 and became a cabinet minister in 1970 as the Secretary of State for Education and Science. In 1975 she was elected as Leader of the Conservative Party and so became Leader of the Opposition. Following the Conservative victory in the General Election in 1979, Margaret Thatcher became the first woman Prime Minister of the UK. She was the longest-serving Prime Minister of the 20th century, remaining in Office until 1990. During her premiership, there were a number of important economic reforms within the UK. She worked closely with the United States President, Ronald Reagan, and was one of the first Western leaders to recognise and welcome the changes in the leadership of the Soviet Union which eventually led to the end of the Cold War.

Margaret Thatcher, Britain’s first woman Prime Minister, led the Conservative government from 1979 to 1990. The government made structural changes to the economy through the privatisation of nationalised industries and imposed legal controls on trade union powers. Deregulation saw a great increase in the role of the City of London as an international centre for investments, insurance and other financial services. Traditional industries, such as shipbuilding and coal mining, declined. In 1982, Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands, a British overseas territory in the South Atlantic. A naval taskforce was sent from the UK and military action led to the recovery of the islands. John Major was Prime Minister after Mrs Thatcher, and helped establish the Northern Ireland peace process.

Roald Dahl (1916–90)

Roald Dahl was born in Wales to Norwegian parents. He served in the Royal Air Force during the Second World War. It was during the 1940s that he began to publish books and short stories. He is most well known for his children’s books, although he also wrote for adults. Dahl’s short stories are known for their unexpected endings, and his children’s books for their unsentimental, macabre, often darkly comic mood, featuring villainous adult enemies of the child characters.

His books champion the kindhearted and feature an underlying warm sentiment. His works for children include James and the Giant Peach, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Matilda, The Witches, Fantastic Mr Fox, The BFG, The Twits, and George’s Marvellous Medicine. His adult works include Tales of the Unexpected.

VIII. LABOUR GOVERNMENT (1997-2010)

In 1997 the Labour Party led by Tony Blair was elected. The Blair government introduced a Scottish Parliament and a Welsh Assembly. The Scottish Parliament has substantial powers to legislate. The Welsh Assembly was given fewer legislative powers but considerable control over public services. In Northern Ireland, the Blair government was able to build on the peace process, resulting in the Good Friday Agreement signed in 1998. The Northern Ireland Assembly was elected in 1999 but suspended in 2002. It was not reinstated until 2007. Most paramilitary groups in Northern Ireland have decommissioned their arms and are inactive. Gordon Brown took over as Prime Minister in 2007. The Labour Party won the 1997 general election with a landslide majority of 179; it was the largest Labour majority ever, and at the time the largest swing to a political party achieved since 1945. Over the next decade, a wide range of progressive social reforms were enacted, with millions lifted out of poverty during Labour’s time in office largely as a result of various tax and benefit reforms.

Among the early acts of Blair’s government were the establishment of the national minimum wage, the devolution of power to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, major changes to the regulation of the banking system, and the re-creation of a citywide government body for London, the Greater London Authority, with its own elected-Mayor.

Combined with a Conservative opposition that had yet to organise effectively under William Hague, and the continuing popularity of Blair, Labour went on to win the 2001 election with a similar majority, dubbed the “quiet landslide” by the media. In 2003 Labour introduced tax credits, government top-ups to the pay of low-wage workers.

A perceived turning point was when Blair controversially allied himself with US President George W. Bush in supporting the Iraq War, which caused him to lose much of his political support. The UN Secretary-General, among many, considered the war illegal and a violation of the UN Charter. The Iraq War was deeply unpopular in most western countries, with Western governments divided in their support and under pressure from worldwide popular protests. The decisions that led up to the Iraq war and its subsequent conduct were the subject of Sir John Chilcot’s Iraq Inquiry (commonly referred to as the “Chilcot report”).

In the 2005 general election, Labour was re-elected for a third term, but with a reduced majority of 66 and popular vote of only 35.2%, the lowest percentage of any majority government in British history. During this election, proposed controversial posters by Alastair Campbell where opposition leader Michael Howard and shadow chancellor Oliver Letwin, who are both Jewish, were depicted as flying pigs were criticised as being anti-Semitic. The posters were referring to the expression ‘when pigs fly’, to suggest that Tory election promises were unrealistic. In response, Campbell said that the posters were not in “any way shape or form” intended to be anti-Semitic.

Blair announced in September 2006 that he would quit as leader within the year, though he had been under pressure to quit earlier than May 2007 in order to get a new leader in place before the May elections which were expected to be disastrous for Labour. In the event, the party did lose power in Scotland to a minority Scottish National Party government at the 2007 elections and, shortly after this, Blair resigned as Prime Minister and was replaced by his Chancellor, Gordon Brown. Although the party experienced a brief rise in the polls after this, its popularity soon slumped to its lowest level since the days of Michael Foot. During May 2008, Labour suffered heavy defeats in the London mayoral election, local elections and the loss in the Crewe and Nantwich by-election, culminating in the party registering its worst ever opinion poll result since records began in 1943, of 23%, with many citing Brown’s leadership as a key factor. Membership of the party also reached a low ebb, falling to 156,205 by the end of 2009: over 40 per cent of the 405,000 peak reached in 1997 and thought to be the lowest total since the party was founded.

Finance proved a major problem for the Labour Party during this period; a “cash for peerages” scandal under Blair resulted in the drying up of many major sources of donations. Declining party membership, partially due to the reduction of activists’ influence upon policy-making under the reforms of Neil Kinnock and Blair, also contributed to financial problems. Between January and March 2008, the Labour Party received just over £3 million in donations and were £17 million in debt; compared to the Conservatives’ £6 million in donations and £12 million in debt. These debts eventually mounted to £24.5 million, and were finally fully repaid in 2015.

In the 2010 general election on 6 May that year, Labour with 29.0% of the vote won the second largest number of seats (258). The Conservatives with 36.5% of the vote won the largest number of seats (307), but no party had an overall majority, meaning that Labour could still remain in power if they managed to form a coalition with at least one smaller party. However, the Labour Party would have had to form a coalition with more than one other smaller party to gain an overall majority; anything less would result in a minority government.

On 10 May 2010, after talks to form a coalition with the Liberal Democrats broke down, Brown announced his intention to stand down as Leader before the Labour Party Conference but a day later resigned as both Prime Minister and party leader.

CONFLICTS IN AFGANISTAN AND IRAQ

Throughout the 1990s, Britain played a leading role in coalition forces involved in the liberation of Kuwait, following the Iraqi invasion in 1990, and the conflict in the Former Republic of Yugoslavia. Since 2000, British armed forces have been engaged in the global fight against international terrorism and against the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, including operations in Afghanistan and Iraq. British combat troops left Iraq in 2009.

The UK operated in Afghanistan till 2021 as part of the United Nations (UN) mandated 50-nation International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) coalition and at the invitation of the Afghan government. ISAF worked to ensure that Afghan territory can never again be used as a safe haven for international terrorism, where groups such as Al Qa’ida could plan attacks on the international community.

IX. COALITION GOVERNMENTS AND BREXIT FROM 2010 -2020

In May 2010, and for the first time in the UK since February 1974, no political party won an overall majority in the General Election. The Conservative and Liberal Democrat parties formed a coalition and the leader of the Conservative Party, David Cameron, became Prime Minister.

David Cameron formed the second Cameron ministry, the first Conservative Party majority government since 1996, following the 2015 general election after being invited by Queen Elizabeth II to form a government. Prior to the election Cameron had led the Cameron–Clegg coalition, a coalition government that consisted of members of the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats, with Liberal Democrat leader Nick Clegg as Deputy Prime Minister.#

Following the vote to leave at the EU referendum on the morning of 24 June, Cameron said that he would resign as Prime Minister after a new leader of the Conservative Party was chosen after the party conference in the autumn. It was announced on 11 July 2016 that he would resign on 13 July and be succeeded by Home Secretary Theresa May. The UK voted by a margin of 51.9% to 48.1% to leave the European Union. David Cameron was succeeded as Prime Minister after the referendum by Theresa May on 13 July 2016. She in turn was succeeded by Boris Johnson on 24 July 2019. The UK formally left the European Union on 31 January 2020.