I. WAR AT HOME AND ABROAD

Broadly speaking, the Middle Ages (or medieval period) spans a thousand years, from the end of the Roman Empire in AD 476 up until 1485. However, the focus here is on the period after the Norman Conquest.

The period after the Norman Conquest up until about 1485 is called the Middle Ages (or the medieval period). It was a time of almost constant war. The English kings fought with the Welsh, Scottish and Irish noblemen for control of their lands. In Wales, the English were able to establish their rule. In 1284 King Edward I of England introduced the Statute of Rhuddlan, which annexed Wales to the Crown of England. Huge castles, including Conwy and Caernarvon, were built to maintain this power. By the middle of the 15th century the last Welsh rebellions had been defeated. English laws and the English language were introduced. Edward’s armies were defeated when they first crossed Offas’s Dyke into Wales. The English king’s determination to crush his opposition, his enormous expenditure on troops and supplies and resistance to Llywelyn from minor Welsh princes who were jealous of his rule, soon meant that the small Welsh forces were forced into their mountain strongholds. At the Treaty of Aberconwy of 1287, Llywelyn was forced to concede much of his territories east of the River Conwy. Edward then began his castle-building campaign, beginning with Flint right on the English border and extending to Builth in mid-Wales.

At the Statute of Rhuddlan, 1284, Wales was divided up into English counties; the English court pattern set firmly in place, and for all intents and purposes, Wales ceased to exist as a political unit. The situation seemed permanent when Edward followed up his castle building program by his completion of Caernarfon, Conwy and Harlech. In 1300, Edward made his son (born at Caernarfon castle, in that mighty fortress overlooking the Menai Straits in Gwynedd) “Prince of Wales.” The powerful king could now turn his attention to those other troublemakers, the Scots.

In Scotland, the English kings were less successful. In 1314 the Scottish, led by Robert the Bruce, defeated the English at the Battle of Bannockburn, and Scotland remained unconquered by the English. At the beginning of the Middle Ages, Ireland was an independent country. The English first went to Ireland as troops to help the Irish king and remained to build their own settlements. By 1200, the English ruled an area of Ireland known as the Pale, around Dublin. Some of the important lords in other parts of Ireland accepted the authority of the English king. During the Middle Ages, the English kings also fought a number of wars abroad. Many knights took part in the Crusades, in which European Christians fought for control of the Holy Land. English kings also fought a long war with France, called the Hundred Years War (even though it actually lasted 116 years). One of the most famous battles of the Hundred Years War was the Battle of Agincourt in 1415, where King Henry V’s vastly outnumbered English army defeated the French. The English left France in the 1450s.

The Normans used a system of land ownership known as feudalism. The king gave land to his lords in return for help in war. Landowners had to send certain numbers of men to serve in the army. Some peasants had their own land but most were serfs. They had a small area of their lord’s land where they could grow food. In return, they had to work for their lord and could not move away. The same system developed in southern Scotland. In the north of Scotland and Ireland, land was owned by members of the ‘clans’ (prominent families).

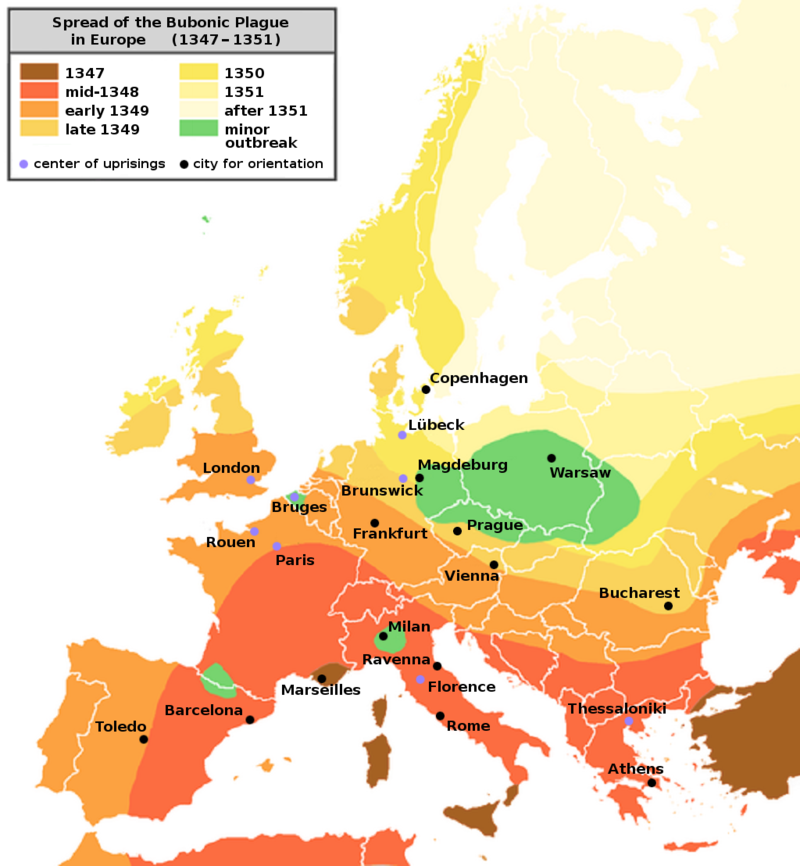

In 1348, a disease, probably a form of plague, came to Britain. This was known as the Black Death. One third of the population of England died and a similar proportion in Scotland and Wales. This was one of the worst disasters ever to strike Britain. Following the Black Death, the smaller population meant there was less need to grow cereal crops. There were labour shortages and peasants began to demand higher wages. New social classes appeared, including owners of large areas of land (later called the gentry), and people left the countryside to live in the towns. In the towns, growing wealth led to the development of a strong middle class. In Ireland, the Black Death killed many in the Pale and, for a time, the area controlled by the English became smaller.

II. LEGAL AND POLITICAL CHANGES

In the Middle Ages, Parliament began to develop into the institution it is today. Its origins can be traced to the king’s council of advisers, which included important noblemen and the leaders of the Church. There were few formal limits to the king’s power until 1215. In that year, King John was forced by his noblemen to agree to a number of demands. The result was a charter of rights called the Magna Carta (which means the Great Charter). The Magna Carta established the idea that even the king was subject to the law. It protected the rights of the nobility and restricted the king’s power to collect taxes or to make or change laws. In future, the king would need to involve his noblemen in decisions. In England, parliaments were called for the king to consult his nobles, particularly when the king needed to raise money. The numbers attending Parliament increased and two separate parts, known as Houses, were established. The nobility, great landowners and bishops sat in the House of Lords. Knights, who were usually smaller landowners, and wealthy people from towns and cities were elected to sit in the House of Commons. Only a small part of the population was able to join in electing the members of the Commons.

A similar Parliament developed in Scotland. It had three Houses, called Estates: the lords, the commons and the clergy.

This was also a time of development in the legal system. The principle that judges are independent of the government began to be established. In England, judges developed ‘common law’ by a process of precedence (that is, following previous decisions) and tradition. In Scotland, the legal system developed slightly differently and laws were ‘codified’ (that is, written down).

III. A DISTINCT IDENTITY

The Middle Ages saw the development of a national culture and identity. After the Norman Conquest, the king and his noblemen had spoken Norman French and the peasants had continued to speak Anglo-Saxon. Gradually these two languages combined to become one English language. Some words in modern English – for example, ‘park’ and ‘beauty’ – are based on Norman French words. Others – for example, ‘apple’, ‘cow’ and ‘summer’ – are based on Anglo-Saxon words. In modern English there are often words with very similar meanings, one from French and one from Anglo-Saxon. ‘Demand’ (French) and ‘ask’ (Anglo-Saxon) are examples. By 1400, in England, official documents were being written in English, and English had become the preferred language of the royal court and Parliament.

In the years leading up to 1400, Geoffrey Chaucer wrote a series of poems in English about a group of people going to Canterbury on a pilgrimage. The people decided to tell each other stories on the journey, and the poems describe the travellers and some of the stories they told. This collection of poems is called The Canterbury Tales. It was one of the first books to be printed by William Caxton, the first person in England to print books using a printing press. Many of the stories are still popular. Some have been made into plays and television programmes. In Scotland, many people continued to speak Gaelic and the Scots language also developed. A number of poets began to write in the Scots language. One example is John Barbour, who wrote The Bruce about the Battle of Bannockburn.

The Middle Ages also saw a change in the type of buildings in Britain. Castles were built in many places in Britain and Ireland, partly for defence. Today many are in ruins, although some, such as Windsor and Edinburgh, are still in use. Great cathedrals – for example, Lincoln Cathedral – were also built, and many of these are still used for worship. Several of the cathedrals had windows of stained glass, telling stories about the Bible and Christian saints. The glass in York Minster is a famous example.

During this period, England was an important trading nation. English wool became a very important export. People came to England from abroad to trade and also to work. Many had special skills, such as weavers from France, engineers from Germany, glass manufacturers from Italy and canal builders from Holland.

IV. THE WAR OF THE ROSES

The symbol of the House of Tudors. A white rose inside of a red rose. In 1455, a civil war was begun to decide who should be king of England. It was fought between the supporters of two families: the House of Lancaster and the House of York. This war was called the Wars of the Roses, because the symbol of Lancaster was a red rose and the symbol of York was a white rose. The war ended with the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485. King Richard III of the House of York was killed in the battle and Henry Tudor, the leader of the House of Lancaster, became King Henry VII. Henry then married King Richard’s niece, Elizabeth of York, and united the two families. Henry was the first king of the House of Tudor. The symbol of the House of Tudor was a red rose with a white rose inside it as a sign that the Houses of York and Lancaster were now allies.